Data Neuroscience Overview

Contents

10. Data Neuroscience Overview¶

10.1. NSCI 801 - Quantitative Neuroscience¶

Gunnar Blohm

10.1.1. Outline¶

Promises and limitations of Data Neuroscience

Data Organization

formats

data bases

intro to ML

dimensionality reduction

classification

decoding

10.1.2. Promises and limitations of Data Neuroscience¶

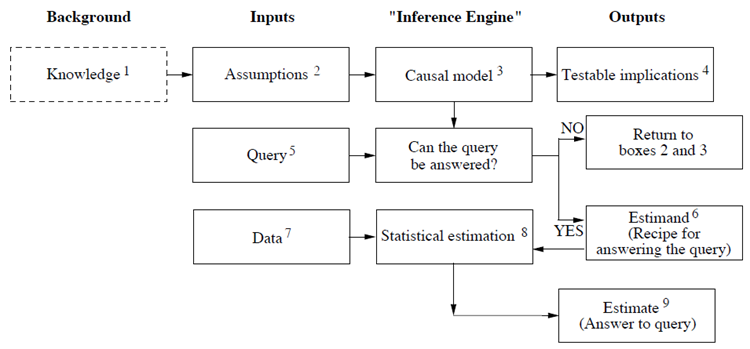

“[…] data are profoundly dumb. Data can tell you that the people who took a medicine recovered faster than people who did not take it, but they can’t tell you why.” (Pearl, in “the book of why”)

Data alone does not give you the answer! But data is important when you have the right question and hypothesis (= model)…

10.1.3. So what can data neuroscience do for us?¶

Here are some examples…

look for structure in really complicated data (= pattern recognition)

automatically extract information from the data (= data mining)

simplify data with lots of redundancy (= dimensionality reduction)

more data = possibility to apply larger statistical models (= curve fitting)

e.g. high-dimensional correlations (= decoding)

e.g. find differences in data (= classification)

10.1.4. Data organization¶

In order to take advantage of big data in neuroscience, we need to organize our data well!

is it scalable, flexible, future-proof?

does it integrate with other data (e.g. repositories)?

is it documented enough to be re-usable?

The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship: Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability

Also check out the NSCI800 lectures on Open Science: Lecture 1 and Lecture 2

10.1.5. Intro to ML¶

Machine learning vs. statistics: how are they complementary?

“Statistics is the study of making strong inferences on few variables from small amounts of noisy data. Machine learning is the study of discovering structured relationships between lots of variables with large amounts of data” (Jordan)

statistics is typically concerned with inferences about parameters of given functional relationships

inferences about variables, while taking uncertainty into account

requires explicit knowledge about the data sampling process

machine learning is concerned with inferences about the functional relationships per se

inference about higher-order interactions, functions, or mappings among variables

makes only weak qualitative assumptions about the data generation process

In this way, one might argue that machine learning is qualitatively similar to human intuition, which likewise enables researchers to make reasonable hypotheses regarding functional relationships among variables, albeit simple ones.

10.1.6. Intro to ML¶

ML is wide field and we can only have a brief glimpse here… but check out further readings if you want to learn more!

Good news! You already know how to perform regressions using ML!

So here we will cover the following:

classification & regularization

dimensionality reduction

decoding

10.1.7. Classification and regularization¶

(adapted from NMA W1D4 tutorial 2)

There are many ways to do classification:

neural network

Bayesian classifier

logistic regression (special case of GLM)

…

Here we’ll use logistic regression.

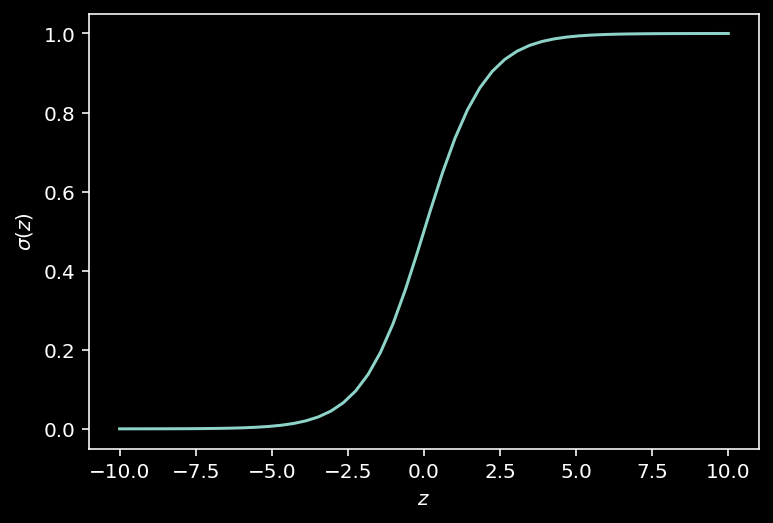

10.1.8. Logistic regression¶

Logistic Regression is a binary classification model. It is a GLM with a logistic link function and a Bernoulli (i.e. coinflip) noise model.

with parameter set \(\theta\)

Goal: find paramter set \(\theta\) that best maps \(x\) onto \(y\). We’ll use the popular ML library scikit-learn.

Note: we need a training set for that…

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

from sklearn.model_selection import cross_val_score

import ipywidgets as widgets

%matplotlib inline

%config InlineBackend.figure_format = 'retina'

plt.style.use('dark_background')

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ModuleNotFoundError Traceback (most recent call last)

Input In [1], in <cell line: 1>()

----> 1 import numpy as np

2 import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

4 from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'numpy'

#@title Helper functions

def plot_weights(models, sharey=True):

"""Draw a stem plot of weights for each model in models dict."""

n = len(models)

f = plt.figure(figsize=(10, 2.5 * n))

axs = f.subplots(n, sharex=True, sharey=sharey)

axs = np.atleast_1d(axs)

for ax, (title, model) in zip(axs, models.items()):

ax.margins(x=.02)

stem = ax.stem(model.coef_.squeeze(), use_line_collection=True)

stem[0].set_marker(".")

stem[0].set_color(".5")

stem[1].set_linewidths(.5)

stem[1].set_color(".5")

stem[2].set_visible(False)

ax.axhline(0, color="C3", lw=3)

ax.set(ylabel="Weight", title=title)

ax.set(xlabel="Neuron (a.k.a. feature)")

f.tight_layout()

def plot_function(f, name, var, points=(-10, 10)):

"""Evaluate f() on linear space between points and plot.

Args:

f (callable): function that maps scalar -> scalar

name (string): Function name for axis labels

var (string): Variable name for axis labels.

points (tuple): Args for np.linspace to create eval grid.

"""

x = np.linspace(*points)

ax = plt.figure().subplots()

ax.plot(x, f(x))

ax.set(

xlabel=f'${var}$',

ylabel=f'${name}({var})$'

)

def plot_model_selection(C_values, accuracies):

"""Plot the accuracy curve over log-spaced C values."""

ax = plt.figure().subplots()

ax.set_xscale("log")

ax.plot(C_values, accuracies, marker="o")

best_C = C_values[np.argmax(accuracies)]

ax.set(

xticks=C_values,

xlabel="$C$",

ylabel="Cross-validated accuracy",

title=f"Best C: {best_C:1g} ({np.max(accuracies):.2%})",

)

def plot_non_zero_coefs(C_values, non_zero_l1, n_voxels):

"""Plot the accuracy curve over log-spaced C values."""

ax = plt.figure().subplots()

ax.set_xscale("log")

ax.plot(C_values, non_zero_l1, marker="o")

ax.set(

xticks=C_values,

xlabel="$C$",

ylabel="Number of non-zero coefficients",

)

ax.axhline(n_voxels, color=".1", linestyle=":")

ax.annotate("Total\n# Neurons", (C_values[0], n_voxels * .98), va="top")

#@title Data retrieval and loading

import os

import requests

import hashlib

url = "https://osf.io/r9gh8/download"

fname = "W1D4_steinmetz_data.npz"

expected_md5 = "d19716354fed0981267456b80db07ea8"

if not os.path.isfile(fname):

try:

r = requests.get(url)

except requests.ConnectionError:

print("!!! Failed to download data !!!")

else:

if r.status_code != requests.codes.ok:

print("!!! Failed to download data !!!")

elif hashlib.md5(r.content).hexdigest() != expected_md5:

print("!!! Data download appears corrupted !!!")

else:

with open(fname, "wb") as fid:

fid.write(r.content)

def load_steinmetz_data(data_fname=fname):

with np.load(data_fname) as dobj:

data = dict(**dobj)

return data

def sigmoid(z):

"""Return the logistic transform of z."""

return 1 / (1 + np.exp(-z))

plot_function(sigmoid, "\sigma", "z", (-10, 10))

10.1.9. Data: neural recordings during decision making¶

Steinmetz et al. (2019) dataset. We will decode the mouse’s decision from the neural data using Logistic Regression.

So let’s load the data and have a look…

data = load_steinmetz_data()

for key, val in data.items():

print(key, val.shape)

spikes (276, 691)

choices (276,)

spikes: an array of normalized spike rates with shape(n_trials, n_neurons)choices: a vector of 0s and 1s, indicating the animal’s behavioral response, with lengthn_trials

So let’s define our inputs and outputs for the training set:

y = data["choices"]

X = data["spikes"]

Now we’re ready to perform the Logistic Regression!

10.1.10. Logistic regression¶

Using a Logistic Regression model within scikit-learn is very simple.

# First define the model

log_reg = LogisticRegression(penalty="none")

# Then fit it to data

log_reg.fit(X, y)

# Now we can look at what the classifier predicts

y_pred = log_reg.predict(X)

Next we want to know how well the classifier worked…

def compute_accuracy(X, y, model):

"""Compute accuracy of classifier predictions.

Args:

X (2D array): Data matrix

y (1D array): Label vector

model (sklearn estimator): Classifier with trained weights.

Returns:

accuracy (float): Proportion of correct predictions.

"""

y_pred = model.predict(X)

accuracy = (y == y_pred).mean()

return accuracy

train_accuracy = compute_accuracy(X, y, log_reg)

print(f"Accuracy on the training data: {train_accuracy:.2%}")

Accuracy on the training data: 100.00%

Wow, this is perfect! We’re soooo good… or are we???

What could have gone wrong?

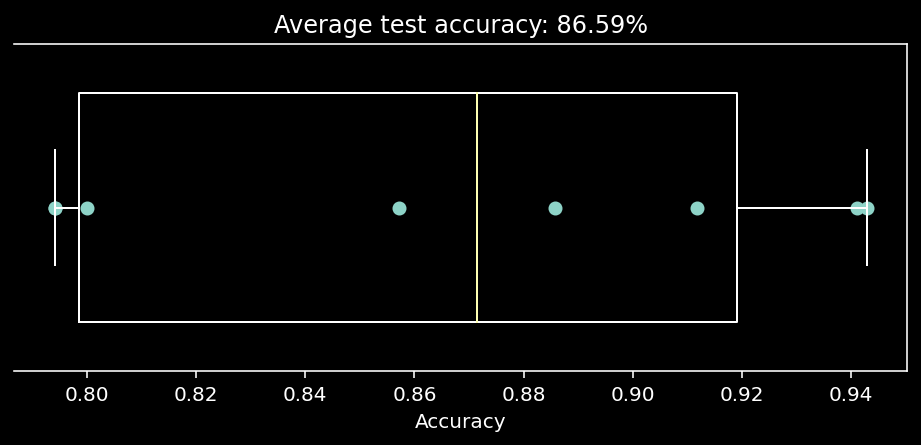

10.1.11. Cross-validating our classifier¶

We’re worried about over-fitting! So let’s cross-validate…

accuracies = cross_val_score(LogisticRegression(penalty='none'), X, y, cv=8) # k=8 crossvalidation

# plot out these `k=8` accuracy scores.

f, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8, 3))

ax.boxplot(accuracies, vert=False, widths=.7)

ax.scatter(accuracies, np.ones(8))

ax.set(

xlabel="Accuracy",

yticks=[],

title=f"Average test accuracy: {accuracies.mean():.2%}"

)

ax.spines["left"].set_visible(False)

Well that’s sobering… what does this mean wrt the 100% accuracy we obtained before?

How can we overcome over-fitting?

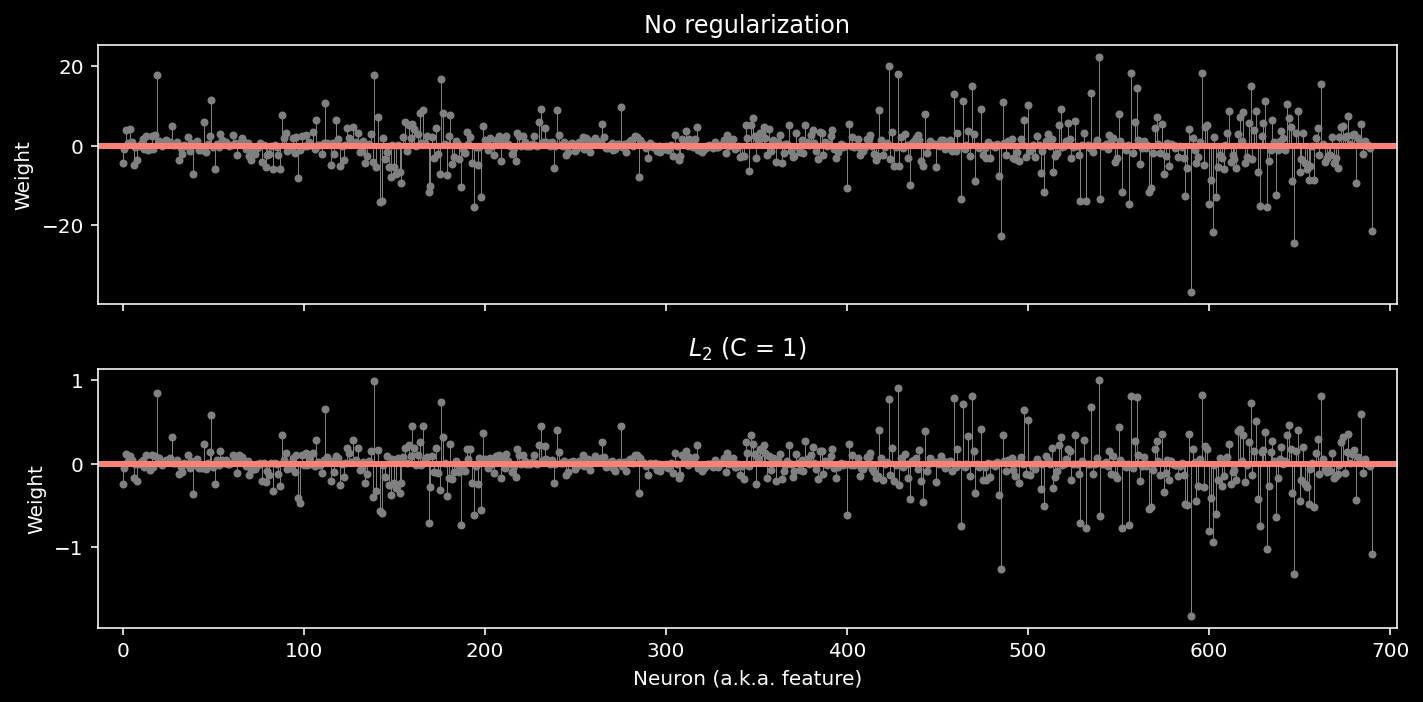

10.1.12. Regularization¶

Regularization is a central concept in ML.

it forces a model to learn a set solutions you a priori believe to be more correct

reduces overfitting (less flexibility to fit idiosyncracies in the training data)

adds model bias, but it’s a good bias: typically it shrinks weights

The 2 main types of regularization are:

\(L_2\) regularization (aka “ridge” penalty): typically produces “dense” weights but of smaller values $\(\color{grey}{-\log\mathcal{L}'(\theta | X, y)=-\log\mathcal{L}(\theta | X, y) +\frac\beta2\sum_i\theta_i^2}\)$

\(L_1\) regularization (aka “Lasso” penalty): tpically produces “sparse” weights (with mostly zero values) $\(\color{grey}{-\log\mathcal{L}'(\theta | X, y)=-\log\mathcal{L}(\theta | X, y) +\frac\beta2\sum_i|\theta_i|}\)$

Let’s have a look…

Note: regularization hyperparameter \(\color{grey}{ C = \frac{1}{\beta}}\)

log_reg_l2 = LogisticRegression(penalty="l2", C=1).fit(X, y)

# now show the two models

models = {

"No regularization": log_reg,

"$L_2$ (C = 1)": log_reg_l2,

}

plot_weights(models, sharey=False)

train_accuracy = compute_accuracy(X, y, log_reg_l2)

print(f"Accuracy on the training data: {train_accuracy:.2%}")

Accuracy on the training data: 97.83%

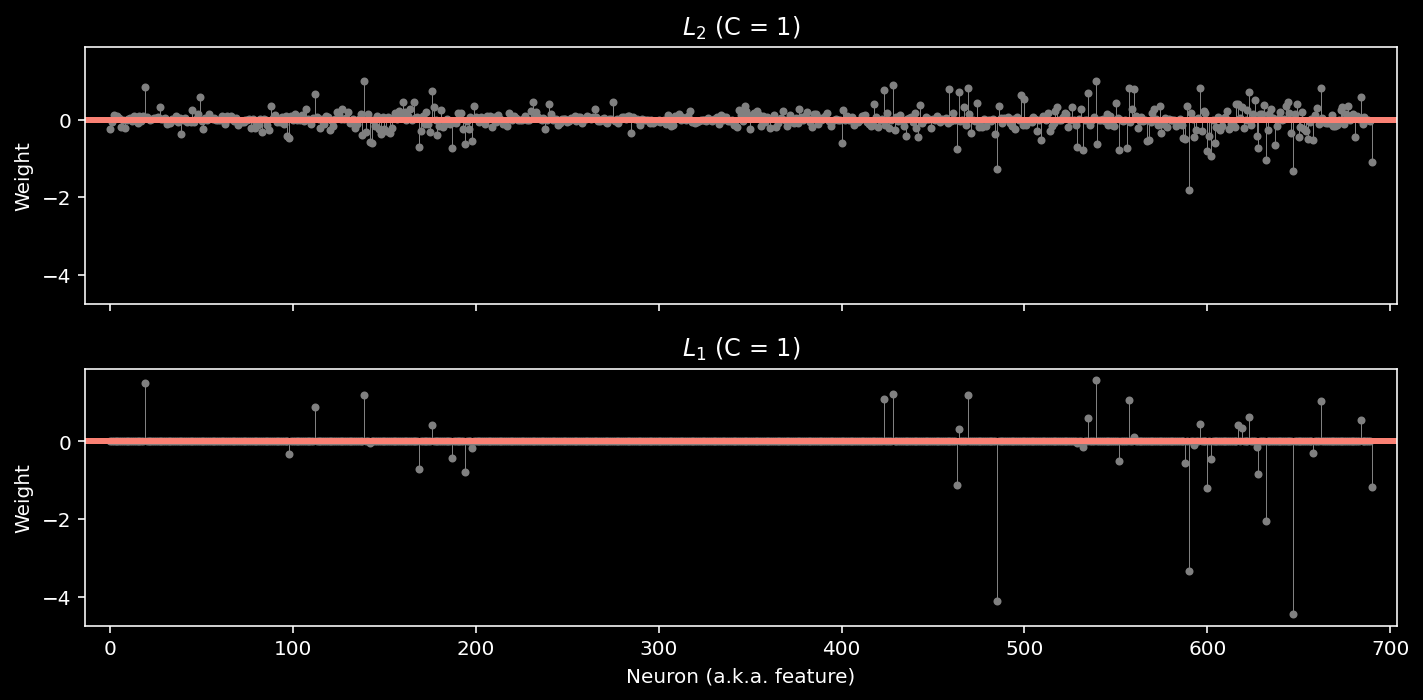

log_reg_l1 = LogisticRegression(penalty="l1", C=1, solver="saga", max_iter=5000)

log_reg_l1.fit(X, y)

models = {

"$L_2$ (C = 1)": log_reg_l2,

"$L_1$ (C = 1)": log_reg_l1,

}

plot_weights(models)

train_accuracy = compute_accuracy(X, y, log_reg_l1)

print(f"Accuracy on the training data: {train_accuracy:.2%}")

Accuracy on the training data: 93.84%

Note: we added two additional parameters: solver=”saga” and max_iter=5000. The LogisticRegression class can use several different optimization algorithms (“solvers”), and not all of them support the L1 penalty. At a certain point, the solver will give up if it hasn’t found a minimum value. The max_iter parameter tells it to make more attempts; otherwise, we’d see an ugly warning about “convergence”.

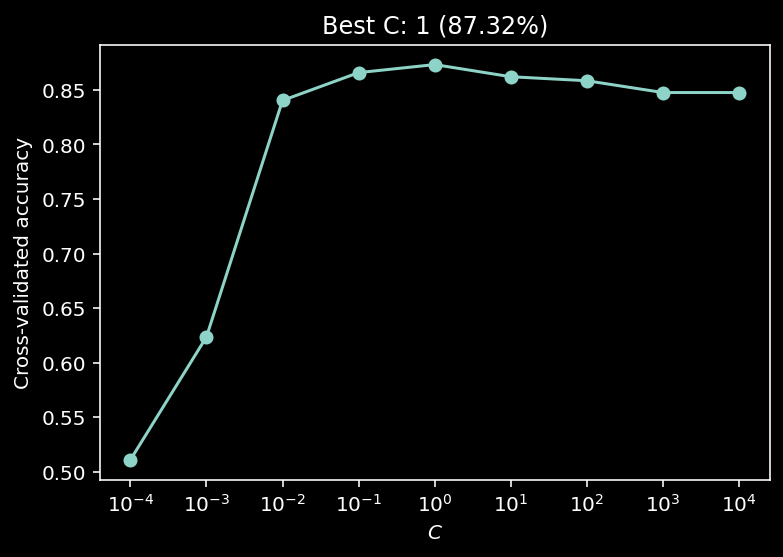

10.1.12.1. So how do we chose the best hyperparameter?¶

We’ll look at the cross-validated classification accuracy…

def model_selection(X, y, C_values):

"""Compute CV accuracy for each C value.

Args:

X (2D array): Data matrix

y (1D array): Label vector

C_values (1D array): Array of hyperparameter values.

Returns:

accuracies (1D array): CV accuracy with each value of C.

"""

accuracies = []

for C in C_values:

# Initialize and fit the model

# (Hint, you may need to set max_iter)

model = LogisticRegression(penalty="l2", C=C, max_iter=5000)

# model = LogisticRegression(penalty="l1", C=C, solver="saga", max_iter=5000)

# Get the accuracy for each test split

accs = cross_val_score(model, X, y, cv=8)

# Store the average test accuracy for this value of C

accuracies.append(accs.mean())

return accuracies

# Use log-spaced values for C

C_values = np.logspace(-4, 4, 9)

accuracies = model_selection(X, y, C_values)

plot_model_selection(C_values, accuracies)

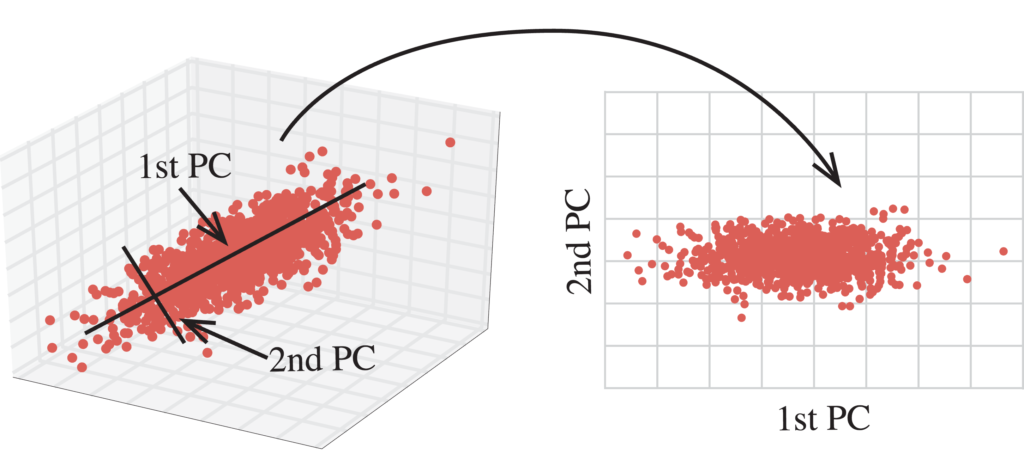

10.1.13. Dimensionality reduction¶

(adapted from Neuromatch Academy W1D5 Tutorial 3)

There are many forms of dimensionality reduction. The idea is that data is NOT uniformly distributed and thus there are some meaningful dimensions of data variability. Dimensionality reduction techniques focus on capturing the dominant dimensions of data variability.

We’ll specifically be learning about Principal Component Analysis (PCA), a linear method producing orthogonal axes.

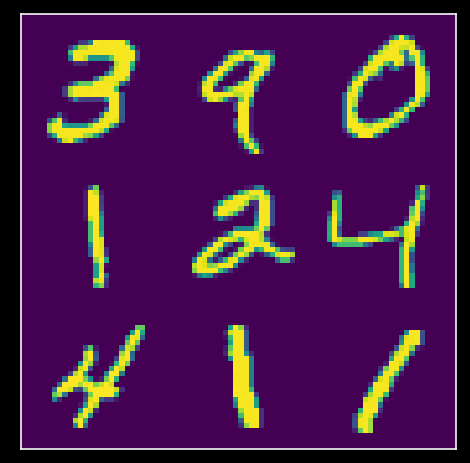

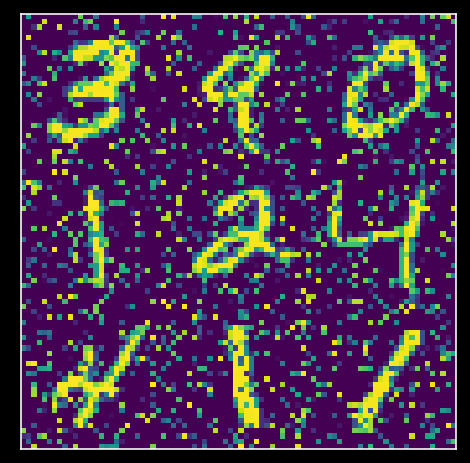

10.1.14. Let’s perform of PCA on MNIST¶

MNIST is a dataset of 70,000 images of handwritten digits.

Each image is a 28x28 pixel grayscale image. For convenience, each 28x28 pixel image is often unravelled into a single 784 (=28*28) element vector, so that the whole dataset is represented as a 70,000 x 784 matrix. Each row represents a different image, and each column represents a different pixel.

Let’s have a look…

# Helper Functions

def plot_variance_explained(variance_explained):

"""

Plots eigenvalues.

Args:

variance_explained (numpy array of floats) : Vector of variance explained

for each PC

Returns:

Nothing.

"""

plt.figure()

plt.plot(np.arange(1, len(variance_explained) + 1), variance_explained)

plt.xlabel('Number of components')

plt.ylabel('Variance explained')

plt.show()

def plot_MNIST_reconstruction(X, X_reconstructed):

"""

Plots 9 images in the MNIST dataset side-by-side with the reconstructed

images.

Args:

X (numpy array of floats) : Data matrix each column

corresponds to a different

random variable

X_reconstructed (numpy array of floats) : Data matrix each column

corresponds to a different

random variable

Returns:

Nothing.

"""

plt.figure()

ax = plt.subplot(121)

k = 0

for k1 in range(3):

for k2 in range(3):

k = k + 1

plt.imshow(np.reshape(X[k, :], (28, 28)),

extent=[(k1 + 1) * 28, k1 * 28, (k2 + 1) * 28, k2 * 28],

vmin=0, vmax=255)

plt.xlim((3 * 28, 0))

plt.ylim((3 * 28, 0))

plt.tick_params(axis='both', which='both', bottom=False, top=False,

labelbottom=False)

ax.set_xticks([])

ax.set_yticks([])

plt.title('Data')

plt.clim([0, 250])

ax = plt.subplot(122)

k = 0

for k1 in range(3):

for k2 in range(3):

k = k + 1

plt.imshow(np.reshape(np.real(X_reconstructed[k, :]), (28, 28)),

extent=[(k1 + 1) * 28, k1 * 28, (k2 + 1) * 28, k2 * 28],

vmin=0, vmax=255)

plt.xlim((3 * 28, 0))

plt.ylim((3 * 28, 0))

plt.tick_params(axis='both', which='both', bottom=False, top=False,

labelbottom=False)

ax.set_xticks([])

ax.set_yticks([])

plt.clim([0, 250])

plt.title('Reconstructed')

plt.tight_layout()

def plot_MNIST_sample(X):

"""

Plots 9 images in the MNIST dataset.

Args:

X (numpy array of floats) : Data matrix each column corresponds to a

different random variable

Returns:

Nothing.

"""

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

k = 0

for k1 in range(3):

for k2 in range(3):

k = k + 1

plt.imshow(np.reshape(X[k, :], (28, 28)),

extent=[(k1 + 1) * 28, k1 * 28, (k2+1) * 28, k2 * 28],

vmin=0, vmax=255)

plt.xlim((3 * 28, 0))

plt.ylim((3 * 28, 0))

plt.tick_params(axis='both', which='both', bottom=False, top=False,

labelbottom=False)

plt.clim([0, 250])

ax.set_xticks([])

ax.set_yticks([])

plt.show()

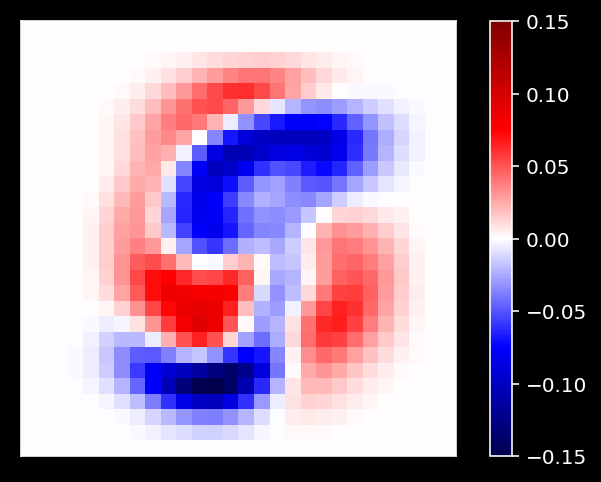

def plot_MNIST_weights(weights):

"""

Visualize PCA basis vector weights for MNIST. Red = positive weights,

blue = negative weights, white = zero weight.

Args:

weights (numpy array of floats) : PCA basis vector

Returns:

Nothing.

"""

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

cmap = plt.cm.get_cmap('seismic')

plt.imshow(np.real(np.reshape(weights, (28, 28))), cmap=cmap)

plt.tick_params(axis='both', which='both', bottom=False, top=False,

labelbottom=False)

plt.clim(-.15, .15)

plt.colorbar(ticks=[-.15, -.1, -.05, 0, .05, .1, .15])

ax.set_xticks([])

ax.set_yticks([])

plt.show()

def add_noise(X, frac_noisy_pixels):

"""

Randomly corrupts a fraction of the pixels by setting them to random values.

Args:

X (numpy array of floats) : Data matrix

frac_noisy_pixels (scalar) : Fraction of noisy pixels

Returns:

(numpy array of floats) : Data matrix + noise

"""

X_noisy = np.reshape(X, (X.shape[0] * X.shape[1]))

N_noise_ixs = int(X_noisy.shape[0] * frac_noisy_pixels)

noise_ixs = np.random.choice(X_noisy.shape[0], size=N_noise_ixs,

replace=False)

X_noisy[noise_ixs] = np.random.uniform(0, 255, noise_ixs.shape)

X_noisy = np.reshape(X_noisy, (X.shape[0], X.shape[1]))

return X_noisy

def change_of_basis(X, W):

"""

Projects data onto a new basis.

Args:

X (numpy array of floats) : Data matrix each column corresponding to a

different random variable

W (numpy array of floats) : new orthonormal basis columns correspond to

basis vectors

Returns:

(numpy array of floats) : Data matrix expressed in new basis

"""

Y = np.matmul(X, W)

return Y

def get_sample_cov_matrix(X):

"""

Returns the sample covariance matrix of data X.

Args:

X (numpy array of floats) : Data matrix each column corresponds to a

different random variable

Returns:

(numpy array of floats) : Covariance matrix

"""

X = X - np.mean(X, 0)

cov_matrix = 1 / X.shape[0] * np.matmul(X.T, X)

return cov_matrix

def sort_evals_descending(evals, evectors):

"""

Sorts eigenvalues and eigenvectors in decreasing order. Also aligns first two

eigenvectors to be in first two quadrants (if 2D).

Args:

evals (numpy array of floats) : Vector of eigenvalues

evectors (numpy array of floats) : Corresponding matrix of eigenvectors

each column corresponds to a different

eigenvalue

Returns:

(numpy array of floats) : Vector of eigenvalues after sorting

(numpy array of floats) : Matrix of eigenvectors after sorting

"""

index = np.flip(np.argsort(evals))

evals = evals[index]

evectors = evectors[:, index]

if evals.shape[0] == 2:

if np.arccos(np.matmul(evectors[:, 0],

1 / np.sqrt(2) * np.array([1, 1]))) > np.pi / 2:

evectors[:, 0] = -evectors[:, 0]

if np.arccos(np.matmul(evectors[:, 1],

1 / np.sqrt(2)*np.array([-1, 1]))) > np.pi / 2:

evectors[:, 1] = -evectors[:, 1]

return evals, evectors

def plot_eigenvalues(evals, limit=True):

"""

Plots eigenvalues.

Args:

(numpy array of floats) : Vector of eigenvalues

Returns:

Nothing.

"""

plt.figure()

plt.plot(np.arange(1, len(evals) + 1), evals)

plt.xlabel('Component')

plt.ylabel('Eigenvalue')

plt.title('Scree plot')

if limit:

plt.show()

from sklearn.datasets import fetch_openml

mnist = fetch_openml(name='mnist_784', as_frame = False)

X = mnist.data

plot_MNIST_sample(X)

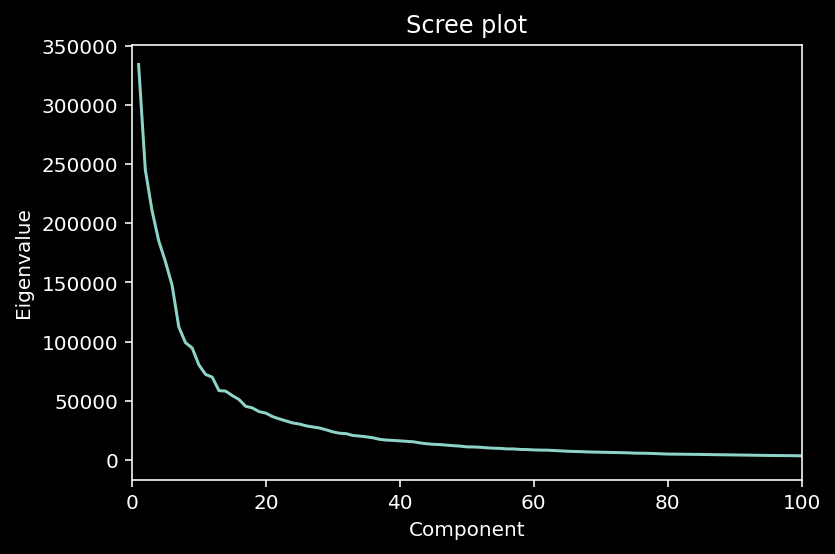

So the MNIST dataset has an extrinsic dimensionality of 784. To make sense of this data, we’ll use dimensionality reduction. But first, we need to determine the intrinsic dimensionality K of the data. One way to do this is to look for an “elbow” in the scree plot, to determine which eigenvalues are signficant.

(“Scree”: collection of broken rock fragments at the base of mountain cliffs)

A scree plot is a line plot of the eigenvalues (= amplitude of variability) of factors or principal components in an analysis.

def pca(X):

"""

Performs PCA on multivariate data. Eigenvalues are sorted in decreasing order

Args:

X (numpy array of floats) : Data matrix each column corresponds to a

different random variable

Returns:

(numpy array of floats) : Data projected onto the new basis

(numpy array of floats) : Vector of eigenvalues

(numpy array of floats) : Corresponding matrix of eigenvectors

"""

X = X - np.mean(X, 0)

cov_matrix = get_sample_cov_matrix(X)

evals, evectors = np.linalg.eigh(cov_matrix)

evals, evectors = sort_evals_descending(evals, evectors)

score = change_of_basis(X, evectors)

return score, evectors, evals

# perform PCA

score, evectors, evals = pca(X)

# plot the eigenvalues

plot_eigenvalues(evals, limit=False)

plt.xlim([0, 100]) # limit x-axis up to 100 for zooming

(0.0, 100.0)

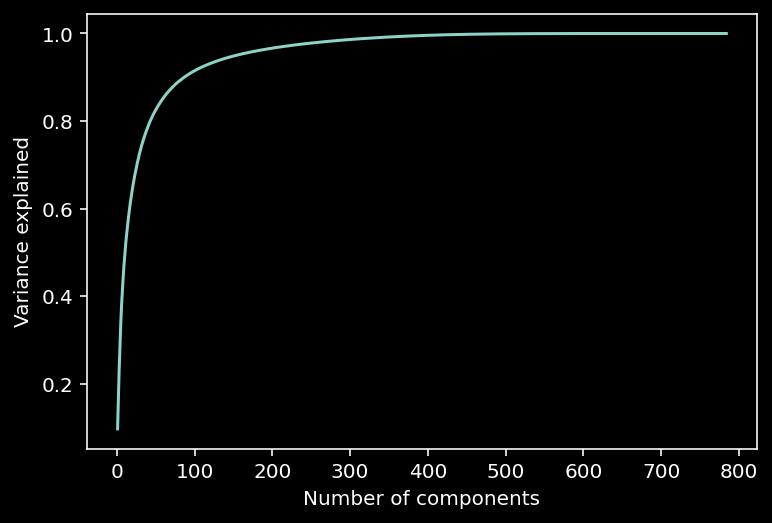

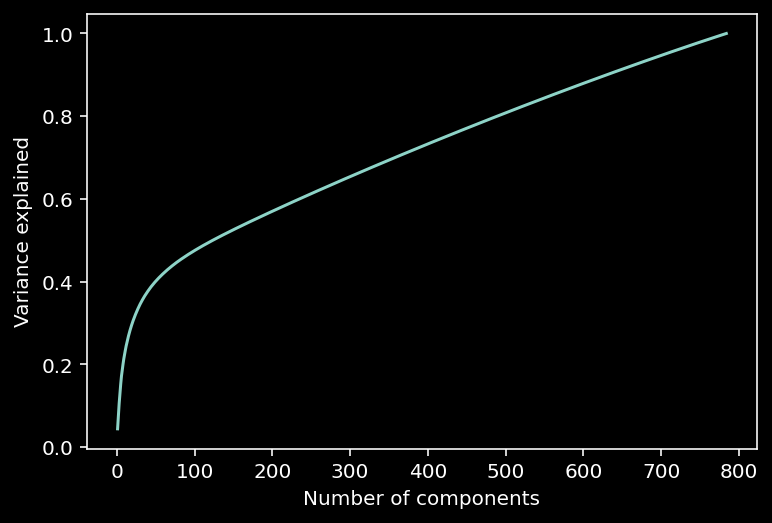

10.1.14.1. Variance explained¶

Note that in the scree plot most values are close to 0. So we can look at the intrinsic dimensionality of the data by analyzing the variance explained.

This can be examined with a cumulative plot of the fraction of the total variance explained by the top \(K\) components, i.e., $\(\color{grey}{\text{var explained} = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^K \lambda_i}{\sum_{i=1}^N \lambda_i}}\)$

The intrinsic dimensionality is often quantified by the \(K\) necessary to explain a large proportion of the total variance of the data (often a defined threshold, e.g., 90%).

def get_variance_explained(evals):

"""

Plots eigenvalues.

Args:

(numpy array of floats) : Vector of eigenvalues

Returns:

Nothing.

"""

# cumulatively sum the eigenvalues

csum = np.cumsum(evals)

# normalize by the sum of eigenvalues

variance_explained = csum / np.sum(evals)

return variance_explained

# calculate the variance explained

variance_explained = get_variance_explained(evals)

plot_variance_explained(variance_explained)

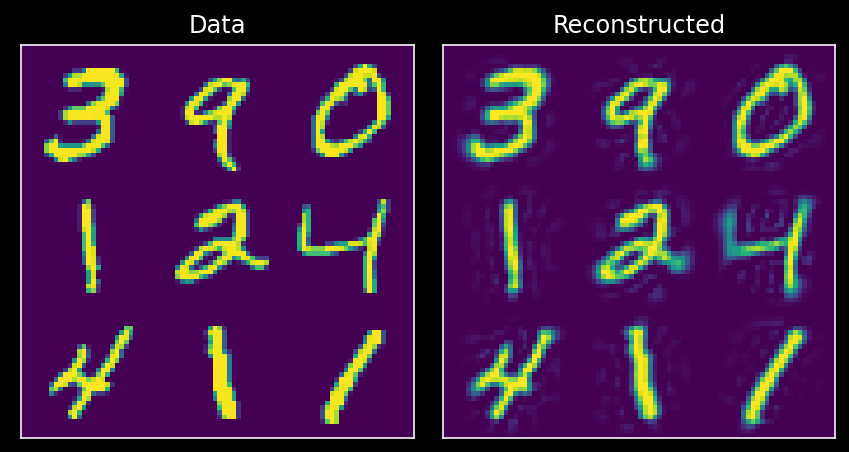

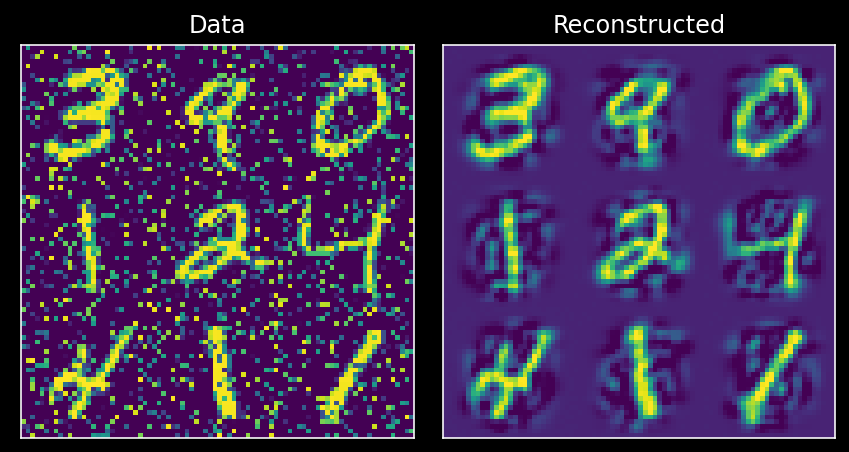

10.1.14.2. Data reconstruction¶

Now we have seen that the top 100 or so principal components of the data can explain most of the variance. We can use this fact to perform dimensionality reduction, i.e., by storing the data using only 100 components rather than the samples of all 784 pixels. Remarkably, we will be able to reconstruct much of the structure of the data using only the top 100 components.

Idea: only use the meaningful dimensions to recreate the data…

def reconstruct_data(score, evectors, X_mean, K):

"""

Reconstruct the data based on the top K components.

Args:

score (numpy array of floats) : Score matrix

evectors (numpy array of floats) : Matrix of eigenvectors

X_mean (numpy array of floats) : Vector corresponding to data mean

K (scalar) : Number of components to include

Returns:

(numpy array of floats) : Matrix of reconstructed data

"""

# Reconstruct the data from the score and eigenvectors

# Don't forget to add the mean!!

X_reconstructed = np.matmul(score[:, :K], evectors[:, :K].T) + X_mean

return X_reconstructed

K = 100

# Reconstruct the data based on all components

X_mean = np.mean(X, 0)

X_reconstructed = reconstruct_data(score, evectors, X_mean, K)

# Plot the data and reconstruction

plot_MNIST_reconstruction(X, X_reconstructed)

10.1.14.3. Visualization of weights¶

One of the cool things we can do now is examine the PCA weights!

# Plot the weights of the first principal component

plot_MNIST_weights(evectors[:, 3])

10.1.14.4. Denoising with PCA¶

Noise is not meaningful variability. I.e., noise will not have a strong Eigenvalue. We can thus use PCA to denoise noisy data!

So let’s do this: add noise to data first:

np.random.seed(2020) # set random seed

X_noisy = add_noise(X, .2)

score_noisy, evectors_noisy, evals_noisy = pca(X_noisy)

variance_explained_noisy = get_variance_explained(evals_noisy)

plot_MNIST_sample(X_noisy)

plot_variance_explained(variance_explained_noisy)

Now we can use PCA to denoise our data by only retaining the top \(K\) principal components that are meaningful. To do so, we’ll project data onto the principal components found in the original dataset.

X_noisy_mean = np.mean(X_noisy, 0)

projX_noisy = np.matmul(X_noisy - X_noisy_mean, evectors)

X_reconstructed = reconstruct_data(projX_noisy, evectors, X_noisy_mean, 100) # use first 50 PCs

plot_MNIST_reconstruction(X_noisy, X_reconstructed)

10.1.15. Decoding¶

(adapted from Neuromatch Academy W3D4 Tutorial 1)

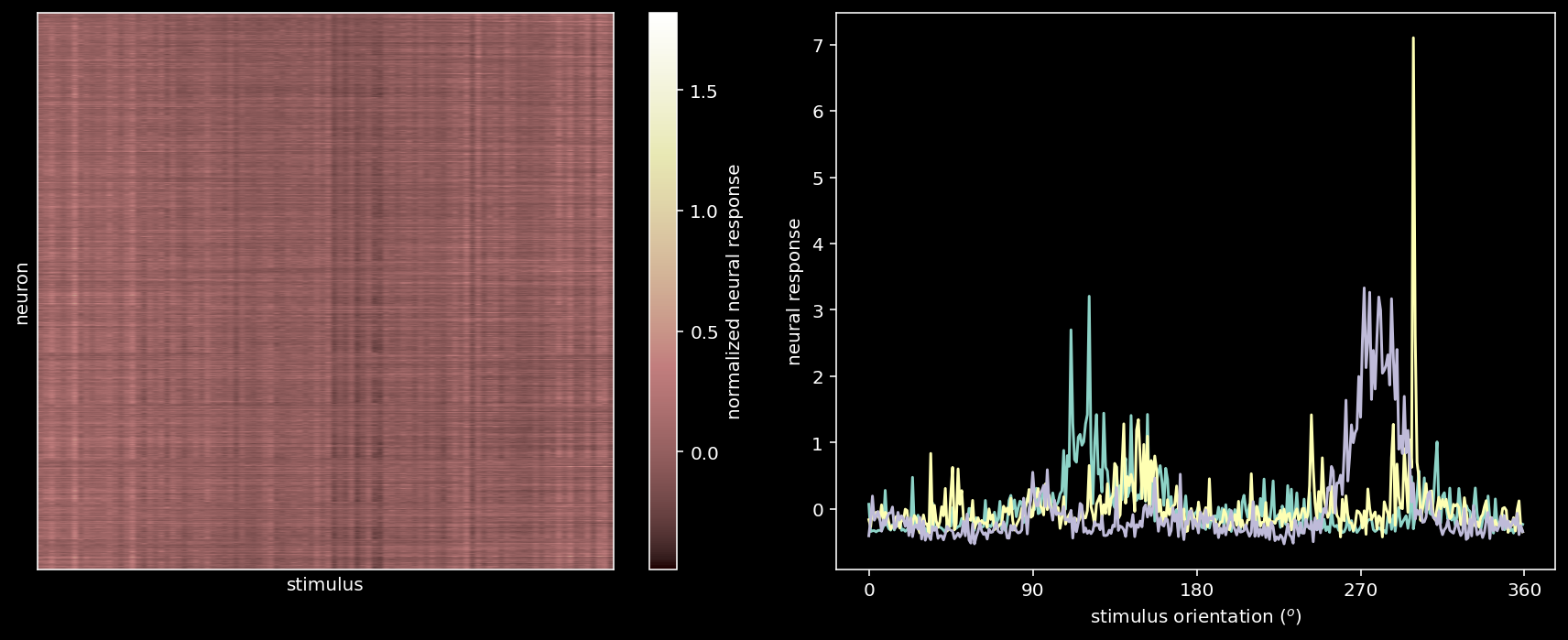

Typical question in neuroscience: how much information does brain area X have about external correlate Y?

We’ll use the Stringer et al. (2019) dataset of ~20,000 simultaneously recorded neurons from mouse V1.

Goal: decode the orientation of the stimulus from the population

(the mouse made a decision on stimulus orientation)

Approach: use deep learning (DL) because

DL thrives with high-dimensional data

DL is great with nonlinear patterns: neurons respond quite differently

DL architectures are very flexible - you can adapt it to maximize decoding

We’ll use pytorch for decoding…

But before getting started, let’s load and look at the data!

import os

import numpy as np

import torch

from torch import nn

from torch import optim

import matplotlib as mpl

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

# Data retrieval and loading

import hashlib

import requests

fname = "W3D4_stringer_oribinned1.npz"

url = "https://osf.io/683xc/download"

expected_md5 = "436599dfd8ebe6019f066c38aed20580"

if not os.path.isfile(fname):

try:

r = requests.get(url)

except requests.ConnectionError:

print("!!! Failed to download data !!!")

else:

if r.status_code != requests.codes.ok:

print("!!! Failed to download data !!!")

elif hashlib.md5(r.content).hexdigest() != expected_md5:

print("!!! Data download appears corrupted !!!")

else:

with open(fname, "wb") as fid:

fid.write(r.content)

# Helper Functions

def load_data(data_name=fname, bin_width=1):

"""Load mouse V1 data from Stringer et al. (2019)

Data from study reported in this preprint:

https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/679324v2.abstract

These data comprise time-averaged responses of ~20,000 neurons

to ~4,000 stimulus gratings of different orientations, recorded

through Calcium imaginge. The responses have been normalized by

spontanous levels of activity and then z-scored over stimuli, so

expect negative numbers. They have also been binned and averaged

to each degree of orientation.

This function returns the relevant data (neural responses and

stimulus orientations) in a torch.Tensor of data type torch.float32

in order to match the default data type for nn.Parameters in

Google Colab.

This function will actually average responses to stimuli with orientations

falling within bins specified by the bin_width argument. This helps

produce individual neural "responses" with smoother and more

interpretable tuning curves.

Args:

bin_width (float): size of stimulus bins over which to average neural

responses

Returns:

resp (torch.Tensor): n_stimuli x n_neurons matrix of neural responses,

each row contains the responses of each neuron to a given stimulus.

As mentioned above, neural "response" is actually an average over

responses to stimuli with similar angles falling within specified bins.

stimuli: (torch.Tensor): n_stimuli x 1 column vector with orientation

of each stimulus, in degrees. This is actually the mean orientation

of all stimuli in each bin.

"""

with np.load(data_name) as dobj:

data = dict(**dobj)

resp = data['resp']

stimuli = data['stimuli']

if bin_width > 1:

# Bin neural responses and stimuli

bins = np.digitize(stimuli, np.arange(0, 360 + bin_width, bin_width))

stimuli_binned = np.array([stimuli[bins == i].mean() for i in np.unique(bins)])

resp_binned = np.array([resp[bins == i, :].mean(0) for i in np.unique(bins)])

else:

resp_binned = resp

stimuli_binned = stimuli

# Return as torch.Tensor

resp_tensor = torch.tensor(resp_binned, dtype=torch.float32)

stimuli_tensor = torch.tensor(stimuli_binned, dtype=torch.float32).unsqueeze(1) # add singleton dimension to make a column vector

return resp_tensor, stimuli_tensor

def plot_data_matrix(X, ax):

"""Visualize data matrix of neural responses using a heatmap

Args:

X (torch.Tensor or np.ndarray): matrix of neural responses to visualize

with a heatmap

ax (matplotlib axes): where to plot

"""

cax = ax.imshow(X, cmap=mpl.cm.pink, vmin=np.percentile(X, 1), vmax=np.percentile(X, 99))

cbar = plt.colorbar(cax, ax=ax, label='normalized neural response')

ax.set_aspect('auto')

ax.set_xticks([])

ax.set_yticks([])

def identityLine():

"""

Plot the identity line y=x

"""

ax = plt.gca()

lims = np.array([ax.get_xlim(), ax.get_ylim()])

minval = lims[:, 0].min()

maxval = lims[:, 1].max()

equal_lims = [minval, maxval]

ax.set_xlim(equal_lims)

ax.set_ylim(equal_lims)

line = ax.plot([minval, maxval], [minval, maxval], color="0.7")

line[0].set_zorder(-1)

def get_data(n_stim, train_data, train_labels):

""" Return n_stim randomly drawn stimuli/resp pairs

Args:

n_stim (scalar): number of stimuli to draw

resp (torch.Tensor):

train_data (torch.Tensor): n_train x n_neurons tensor with neural

responses to train on

train_labels (torch.Tensor): n_train x 1 tensor with orientations of the

stimuli corresponding to each row of train_data, in radians

Returns:

(torch.Tensor, torch.Tensor): n_stim x n_neurons tensor of neural responses and n_stim x 1 of orientations respectively

"""

n_stimuli = train_labels.shape[0]

istim = np.random.choice(n_stimuli, n_stim)

r = train_data[istim] # neural responses to this stimulus

ori = train_labels[istim] # true stimulus orientation

return r, ori

def stimulus_class(ori, n_classes):

"""Get stimulus class from stimulus orientation

Args:

ori (torch.Tensor): orientations of stimuli to return classes for

n_classes (int): total number of classes

Returns:

torch.Tensor: 1D tensor with the classes for each stimulus

"""

bins = np.linspace(0, 360, n_classes + 1)

return torch.tensor(np.digitize(ori.squeeze(), bins)) - 1 # minus 1 to accomodate Python indexing

def plot_decoded_results(train_loss, test_labels, predicted_test_labels):

""" Plot decoding results in the form of network training loss and test predictions

Args:

train_loss (list): training error over iterations

test_labels (torch.Tensor): n_test x 1 tensor with orientations of the

stimuli corresponding to each row of train_data, in radians

predicted_test_labels (torch.Tensor): n_test x 1 tensor with predicted orientations of the

stimuli from decoding neural network

"""

# Plot results

fig, (ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(16, 6))

# Plot the training loss over iterations of GD

ax1.plot(train_loss)

# Plot true stimulus orientation vs. predicted class

ax2.plot(stimuli_test.squeeze(), predicted_test_labels, '.')

ax1.set_xlim([0, None])

ax1.set_ylim([0, None])

ax1.set_xlabel('iterations of gradient descent')

ax1.set_ylabel('negative log likelihood')

ax2.set_xlabel('true stimulus orientation ($^o$)')

ax2.set_ylabel('decoded orientation bin')

ax2.set_xticks(np.linspace(0, 360, n_classes + 1))

ax2.set_yticks(np.arange(n_classes))

class_bins = [f'{i * 360 / n_classes: .0f}$^o$ - {(i + 1) * 360 / n_classes: .0f}$^o$' for i in range(n_classes)]

ax2.set_yticklabels(class_bins);

# Draw bin edges as vertical lines

ax2.set_ylim(ax2.get_ylim()) # fix y-axis limits

for i in range(n_classes):

lower = i * 360 / n_classes

upper = (i + 1) * 360 / n_classes

ax2.plot([lower, lower], ax2.get_ylim(), '-', color="0.7", linewidth=1, zorder=-1)

ax2.plot([upper, upper], ax2.get_ylim(), '-', color="0.7", linewidth=1, zorder=-1)

plt.tight_layout()

# Load data

resp_all, stimuli_all = load_data() # argument to this function specifies bin width

n_stimuli, n_neurons = resp_all.shape

print(f'{n_neurons} neurons in response to {n_stimuli} stimuli')

fig, (ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(2 * 6, 5))

# Visualize data matrix

plot_data_matrix(resp_all[:100, :].T, ax1) # plot responses of first 100 neurons

ax1.set_xlabel('stimulus')

ax1.set_ylabel('neuron')

# Plot tuning curves of three random neurons

ineurons = np.random.choice(n_neurons, 3, replace=False) # pick three random neurons

ax2.plot(stimuli_all, resp_all[:, ineurons])

ax2.set_xlabel('stimulus orientation ($^o$)')

ax2.set_ylabel('neural response')

ax2.set_xticks(np.linspace(0, 360, 5))

plt.tight_layout()

23589 neurons in response to 360 stimuli

Now let’s split our dataset into training set and test set.

# Set random seeds for reproducibility

np.random.seed(4)

torch.manual_seed(4)

# Split data into training set and testing set

n_train = int(0.6 * n_stimuli) # use 60% of all data for training set

ishuffle = torch.randperm(n_stimuli)

itrain = ishuffle[:n_train] # indices of data samples to include in training set

itest = ishuffle[n_train:] # indices of data samples to include in testing set

stimuli_test = stimuli_all[itest]

resp_test = resp_all[itest]

stimuli_train = stimuli_all[itrain]

resp_train = resp_all[itrain]

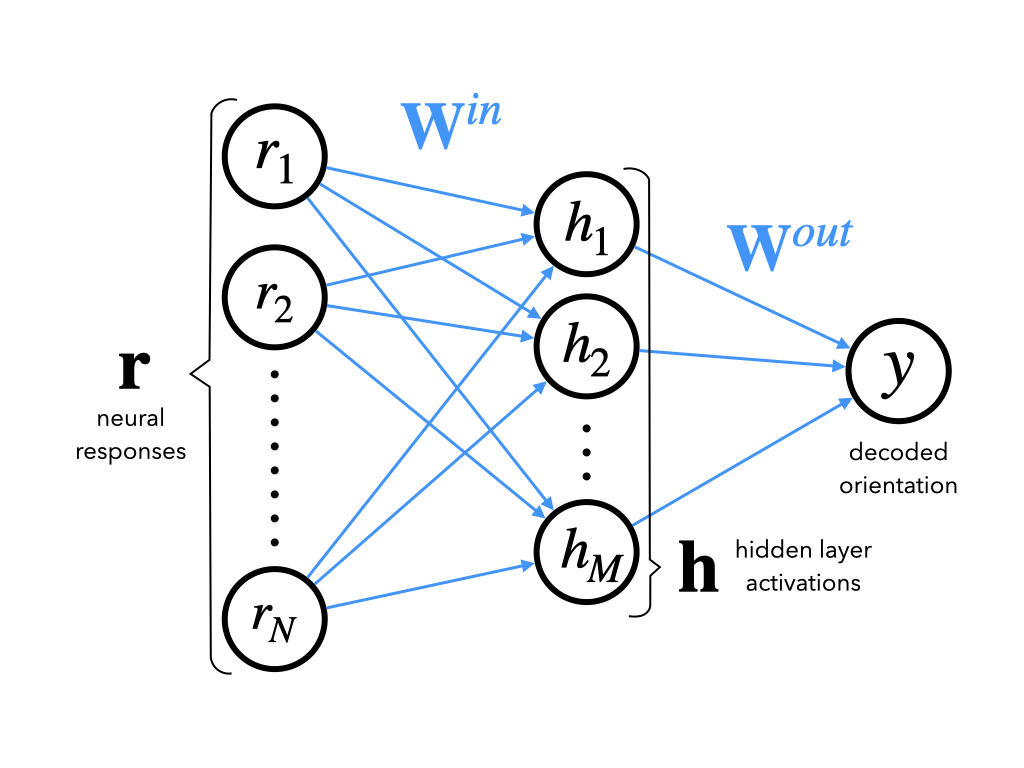

10.1.15.1. Deep feed-forward networks in pytorch¶

We will build a very simple 3-layer network, aka a universal function approximator.

class DeepNet(nn.Module):

"""Deep Network with one hidden layer

Args:

n_inputs (int): number of input units

n_hidden (int): number of units in hidden layer

Attributes:

in_layer (nn.Linear): weights and biases of input layer

out_layer (nn.Linear): weights and biases of output layer

"""

def __init__(self, n_inputs, n_hidden):

super().__init__() # needed to invoke the properties of the parent class nn.Module

self.in_layer = nn.Linear(n_inputs, n_hidden) # neural activity --> hidden units

self.out_layer = nn.Linear(n_hidden, 1) # hidden units --> output

def forward(self, r):

"""Decode stimulus orientation from neural responses

Args:

r (torch.Tensor): vector of neural responses to decode, must be of

length n_inputs. Can also be a tensor of shape n_stimuli x n_inputs,

containing n_stimuli vectors of neural responses

Returns:

torch.Tensor: network outputs for each input provided in r. If

r is a vector, then y is a 1D tensor of length 1. If r is a 2D

tensor then y is a 2D tensor of shape n_stimuli x 1.

"""

h = self.in_layer(r) # hidden representation

y = self.out_layer(h)

return y

Let’s see if this works?

# Set random seeds for reproducibility

np.random.seed(1)

torch.manual_seed(1)

# Initialize a deep network with M=200 hidden units

net = DeepNet(n_neurons, 200)

# Get neural responses (r) to and orientation (ori) to one stimulus in dataset

r, ori = get_data(1, resp_train, stimuli_train) # using helper function get_data

# Decode orientation from these neural responses using initialized network

out = net(r) # compute output from network, equivalent to net.forward(r)

print('decoded orientation: %.2f degrees' % out)

print('true orientation: %.2f degrees' % ori)

decoded orientation: 0.08 degrees

true orientation: 139.00 degrees

It works, but the output is nonsense because we have not trained the network yet!

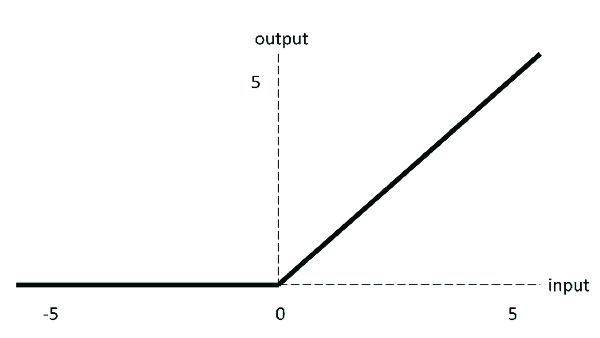

10.1.15.2. Activation functions¶

Our network has purely linear layers so far, i.e. sum of weighted inputs. But to be come a universal function approximator, we need nonlinear activation functions, e.g.

sigmoid

ReLU (Rectivied Linear Units) - we’ll be using this here

class DeepNetReLU(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, n_inputs, n_hidden):

super().__init__() # needed to invoke the properties of the parent class nn.Module

self.in_layer = nn.Linear(n_inputs, n_hidden) # neural activity --> hidden units

self.out_layer = nn.Linear(n_hidden, 1) # hidden units --> output

def forward(self, r):

h = torch.relu(self.in_layer(r))

y = self.out_layer(h)

return y

# Set random seeds for reproducibility

np.random.seed(1)

torch.manual_seed(1)

# Get neural responses (r) to and orientation (ori) to one stimulus in dataset

r, ori = get_data(1, resp_train, stimuli_train)

# Initialize deep network with M=20 hidden units and uncomment lines below

net = DeepNetReLU(n_neurons, 20)

# Decode orientation from these neural responses using initialized network

# net(r) is equivalent to net.forward(r)

out = net(r)

print('decoded orientation: %.2f degrees' % out)

print('true orientation: %.2f degrees' % ori)

decoded orientation: 0.13 degrees

true orientation: 139.00 degrees

This is of course still nonsense. So let’s look at training the network decoder…

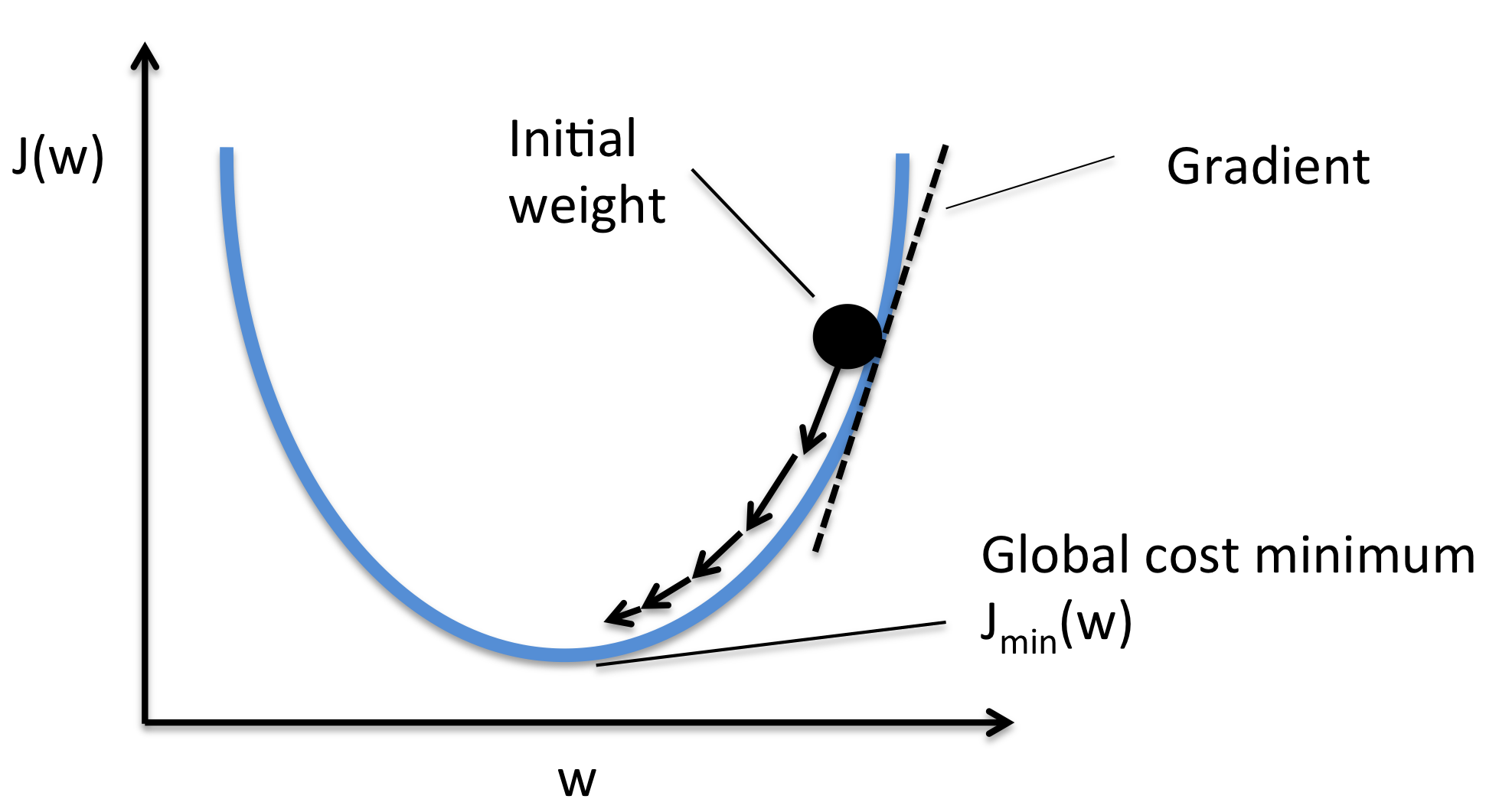

10.1.15.3. Loss function and gradient descent¶

In the same way that we had a loss function (cost function) for model fitting, we need one for our neural network model too. We’ll simply be using the mean squared error (MSE) again. $\(\color{grey}{L = \frac{1}{P}\sum_{n=1}^P \left(y^{(n)} - \tilde{y}^{(n)}\right)^2}\)$ Let’s evaluate the loss for our (untrained network)…

# Set random seeds for reproducibility

np.random.seed(1)

torch.manual_seed(1)

# Initialize a deep network with M=20 hidden units

net = DeepNetReLU(n_neurons, 20)

# Get neural responses to first 20 stimuli in the data set

r, ori = get_data(20, resp_train, stimuli_train)

# Decode orientation from these neural responses

out = net(r)

# Initialize PyTorch mean squared error loss function (Hint: look at nn.MSELoss)

loss_fn = nn.MSELoss()

# Evaluate mean squared error

loss = loss_fn(out, ori)

print('mean squared error: %.2f' % loss)

mean squared error: 42943.74

We can now do gradient descent.

def train(net, loss_fn, train_data, train_labels, n_iter=200, learning_rate=1e-4):

"""Run gradient descent to opimize parameters of a given network

Args:

net (nn.Module): PyTorch network whose parameters to optimize

loss_fn: built-in PyTorch loss function to minimize

train_data (torch.Tensor): n_train x n_neurons tensor with neural

responses to train on

train_labels (torch.Tensor): n_train x 1 tensor with orientations of the

stimuli corresponding to each row of train_data, in radians

n_iter (int): number of iterations of gradient descent to run

learning_rate (float): learning rate to use for gradient descent

"""

# Initialize PyTorch Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) optimizer

optimizer = optim.SGD(net.parameters(), lr=learning_rate)

# Placeholder to save the loss at each iteration

track_loss = []

# Loop over epochs (cf. appendix)

for i in range(n_iter):

# Evaluate loss using loss_fn

out = net(train_data) # compute network output from inputs in train_data

loss = loss_fn(out, train_labels) # evaluate loss function

# Compute gradients

optimizer.zero_grad()

loss.backward()

# Update weights

optimizer.step()

# Store current value of loss

track_loss.append(loss.item()) # .item() needed to transform the tensor output of loss_fn to a scalar

# Track progress

if (i + 1) % (n_iter // 5) == 0:

print(f'iteration {i + 1}/{n_iter} | loss: {loss.item():.3f}')

return track_loss

# Set random seeds for reproducibility

np.random.seed(1)

torch.manual_seed(1)

# Initialize network

net = DeepNetReLU(n_neurons, 20)

# Initialize built-in PyTorch MSE loss function

loss_fn = nn.MSELoss()

# Run GD on data

train_loss = train(net, loss_fn, resp_train, stimuli_train)

# Plot the training loss over iterations of GD

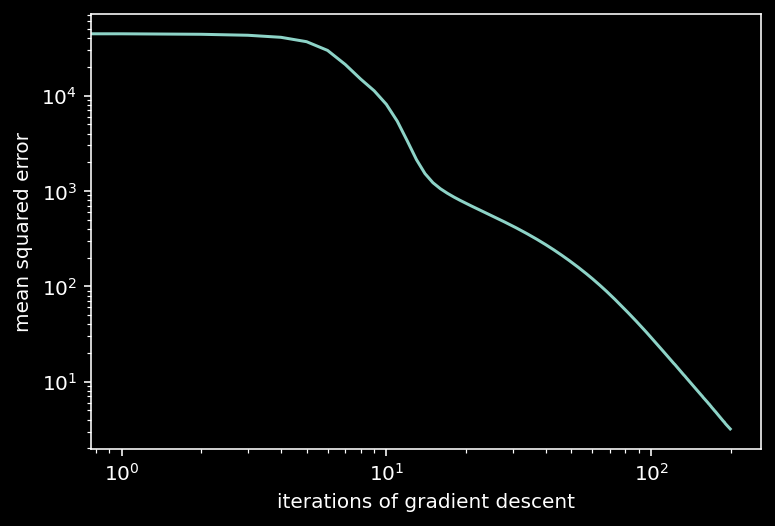

plt.loglog(train_loss)

plt.xlabel('iterations of gradient descent')

plt.ylabel('mean squared error')

plt.show()

iteration 40/200 | loss: 285.460

iteration 80/200 | loss: 58.562

iteration 120/200 | loss: 16.741

iteration 160/200 | loss: 6.620

iteration 200/200 | loss: 3.193

10.1.15.4. Evaluate model performance¶

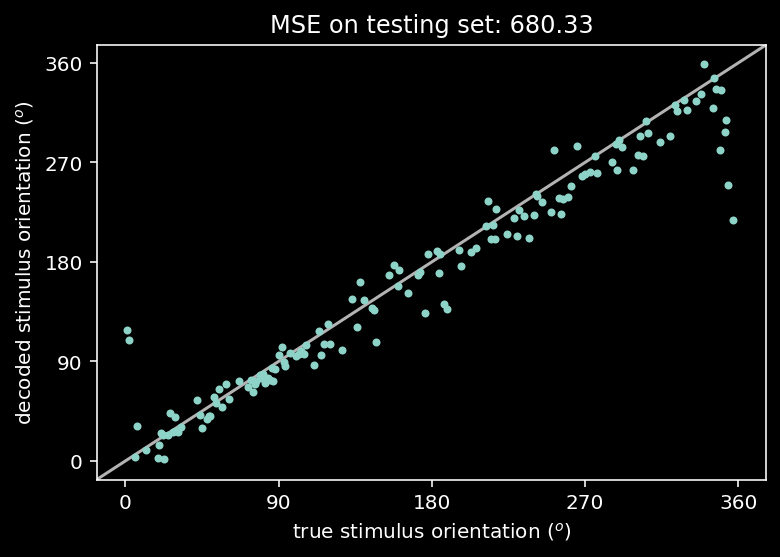

Using the testset, we can now plot the model’s prediction (decoded orientation) over the true orientation.

# evaluate and plot test error

out = net(resp_test) # decode stimulus orientation for neural responses in testing set

ori = stimuli_test # true stimulus orientations

test_loss = loss_fn(out, ori) # MSE on testing set (Hint: use loss_fn initialized in previous exercise)

plt.plot(ori, out.detach(), '.') # N.B. need to use .detach() to pass network output into plt.plot()

identityLine() # draw the identity line y=x; deviations from this indicate bad decoding!

plt.title('MSE on testing set: %.2f' % test_loss.item()) # N.B. need to use .item() to turn test_loss into a scalar

plt.xlabel('true stimulus orientation ($^o$)')

plt.ylabel('decoded stimulus orientation ($^o$)')

axticks = np.linspace(0, 360, 5)

plt.xticks(axticks)

plt.yticks(axticks)

plt.show()